In the second part of “Nonstop Oslo”, Vivienne returns home to Haiti after her four-day romantic adventure in Oslo. Her daughters have gone out with friends and she prays to God for their safe return home amidst increased violence in Haiti. Throughout the first part of the book, she reflects on how difficult life is back home, how uninspired Haitian politicians are, and how the system is so corrupt that the most reprehensible acts are considered “normal” and tolerated by the majority of the people of Haiti. In this installment of my blog, I thought I would talk a little about my beautiful, but endangered, country…

To say that life in Haiti is difficult would be a gross understatement. It is nearly damn impossible. And has been so for years. Just when you think that things cannot possibly get worse, Haiti shows that it indeed can.

But first things first. For those of you who know very little about Haiti, here are some quick and interesting facts:

- Haiti is the first nation of slaves that succeeded in overthrowing French colonial forces, defeating Napoleon’s army, the best in the world at the time, to become the world’s first free Black Republic on January 1, 1804. It had become a beacon of hope, affirming the universal truth that all men are created equal. Haiti welcomed all oppressed citizens of nations everywhere, granting them Haitian citizenship once they reached Haitian shores.

- Imperialist countries refused to recognize Haiti’s independence as that would send a dangerous signal around the world and help squash the slavery movement which was quite profitable for them. Once called “La Perle des Antilles” ( The Jewel of the Antilles), Haiti provided as much as 50% of the GNP of France in the 1750s. The French imported sugar, coffee, cocoa, tobacco, cotton, indigo, and other exotic goods from this beautiful and proud island in the Caribbean. France, feeling victimized by Haiti’s extraordinary feat and the massacre of its citizens on the island that followed these dramatic events, demanded reparation in the sum of 150 million gold francs for the loss of its slaves and the profitable business they brought working on plantations in the world’s richest colony. Under the menace of 14 warships with more than 500 canons pointed at the island, France forced then Haitian president Boyer to accept payment of this “debt” if France was to recognize Haiti’s independence. It is reported that the famous Eiffel Tower in beautiful Paris was built with monies from Haiti’s reparation to France. Today, Haiti is the poorest nation in the western hemisphere.

- Surprisingly (or not), this interesting part of French/Haitian history is not taught in French classrooms. Only recently has an ex-President of France advocated for this truth to be taught in schools.

- The Palais Sans Souci, the principal residence of Henri I, King of Haiti, in Milot, and a few miles away, La Citadelle Laferrière, a huge fortress protruding from the northern mountains of Haiti overlooking the bay as part of Haiti’s military strategy to warn off and destroy Napoleon’s army, are two of Haiti’s proud monuments that speak of its past grandeur.

- Haiti was instrumental in helping other countries fight for their freedom and consolidate their territory, including the United States of America. Early in the 19th century, Haiti helped modern-day northwest Brazil, Guyana, Venezuela, Ecuador, Colombia, Panama, northern Peru, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Bolivia to obtain their independence.

- Between 1876 and the 1970s, various tramways and railways ran in the country. A tram network operated in the capital, Port-au-Prince, between 1897 and 1932. Only vestiges of these rails exists today. Haiti’s new generation knows nothing about this. They can’t even imagine it. If I were to tell my daughters that we had well-organized public transportation in my youth, they would surely think I was lying.

- Haiti was a great tourist destination in the mid-1900’s up until around the early 1980s. It was the favorite destination of some of Hollywood’s biggest stars, American writers like James Jones and cartoonist Charles Adams, and English authors like Graham Greene and Sir John Gielgud. Haiti’s famous Hotel Oloffson, named after a Swedish sea captain from Germany, Werner Gustav Oloffson, who turned this magnificent property into a hotel after the American occupation, was the real-life inspiration for the fictional Hotel Trianon in Graham Greene’s 1966 novel, “The Comedians”. Yes, Haiti was occupied by the United States for 30 years, from July 28, 1915 to August 1, 1934.

- If anything was happening in the Caribbean, it happened in Haiti first. Haiti was a place of great cultural happenings, particularly its outstanding 3-day carnival that happened (and still does, but has lost its former glory) every year. Haiti was a major stage for the likes of international greats like Brazilian singer Nelson Ned, Spanish crooner Julio Iglesias, Canadian sensation Claude Valade, and many more. Haiti had a budding film industry and countless movie theaters, including four drive-in cinemas in the capital; it had a roller-skating rink as well as an ice rink. None of those exist today.

- Haiti has known dictatorship under the Duvalier regime from 1957 to 1986, starting with Dr. François Duvalier (a.k.a. Papa Doc) whose brutal rule terrorized and victimized many families in Haiti until his death in 1971. His son, then 18-year-old son, Jean-Claude Duvalier (a.k.a. Baby Doc) would continue his father’s rule until he abdicated in 1986 to avoid bloodshed given the population’s growing discontent with this form of government. Baby Doc’s rule was less violent than that of his father but was characterized by excesses in personal spending and perhaps other reprehensible acts. However, in light of what is going on in Haiti today, none can objectively deny, that during Baby Doc’s rule, life in Haiti was relatively peaceful.

- Haiti also knew rule by a Roman catholic priest, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, elected in Haiti’s first free democratic elections in 1990, organized by Haiti’s only female president, the outstanding jurist Ertha Pascal-Trouillot. His rule began in February 1991 and lasted just a few months until his political discourse prompted the, then, highest ranking officer of the Haitian armed forces, Lieutenant-General Raoul Cédras, to lead a coup-d’état and dispose of Aristide, who sought asylum in the United States. Aristide returned to power in 1994 to finish his mandate, aided by U.S. military forces under ex-President Bill Clinton who dismantled the Haitian army. Aristide was again elected to power in 2001 but was once again ousted by popular rebellion in 2004.

- Haiti was also led by popular Haitian musician turned president, Michel Joseph Martelly, from 2011-2016. Mr. Martelly was a presidential candidate under a peasant political banner until he later formed his own political party “Tèt kale”, known as PHTK. This is the party currently in power.

- Haiti has some of the most beautiful natural beaches in the Caribbean. It has miles of white sand, and black sand in other places. Its majestic mountains provide a natural barrier for a lot of bad weather, but still, the southern tip of the island regularly gets hit by hurricanes causing massive destruction throughout the peninsula. Haiti offers some of the most beautiful landscapes and scenery in this part of the hemisphere. Haiti and the Dominican Republic share this island (known as Hispaniola) and much of their history.

- Haiti produces an award-winning rum from Rhum Barbancourt, and a two-time world champion in the lager beer category, Prestige. The brewery, Brasserie Nationale (BRANA, SA), that produced that outstanding beer is now owned and operated by The Heineken Company.

- In the afternoon of January 12, 2010, a 7.0-magnitude earthquake destroyed much of Port-au-Prince and neighboring towns, killing at least 200,000 people, and plunging an already battered nation into mourning. My own neighborhood of Turgeau was severely hit by the earthquake and its subsequent tremors. Université Quisqueya, a private university just up the street from my house, was the theater of unspeakable tragedy. We could hear the desperate voices of dozens of students wailing from under the debris throughout that first cold night. Most of them did not make it out alive.

Two years ago, Haiti got right back, front and center, in the international news because of three regrettable events: 1) the vicious murder of President Jovenel Moise in his own home on the night of July 6 – 7 , 2) another 7.0-magnitude earthquake in August 2021 in the Southern peninsula of Haiti that left over 2,200 dead and tens of thousands of people homeless and unassisted, and then was immediately followed by a tropical storm that ruthlessly drenched the already vulnerable and homeless population, and 3) extremely violent gangs taking over major sections of Port-au-Prince. Over the ensuing months, things have gotten progressively worse, with the gangs quickly spreading their deadly reach across most of the capital and in the provinces, and terrorizing the population. Kidnappings, murders, and rape are daily occurrences. Families have become impoverished, forced to hand over life savings to ruthless gangs whom no one seems to be able to stop, including the Haitian National Police and the recently re-created army both of which are not nearly as well equipped as the gangs. Prime Minister Ariel Henry’s government seems to be doing very little to control the situation and restore security for the citizens. A high-ranking military officer tearfully and publicly expressed his frustration at not being able to counter these armed groups for lack of resources.

Additionally, Haiti faces the challenge of a chronic gas shortage that has impacted all sectors of the economy, including energy, communications, industrial, food production, retail sectors, bank operations, and water-purifying plants. This recurrent issue has brought all activities across the territory to a virtual stop, adding to Haiti’s extreme poverty and food insecurity. Worse yet, Cholera, which was introduced in Haiti with the arrival of the United Nations peace-keeping mission in 2010, is back with a vengeance and weighing heavily on our already overwhelmed health system. Haiti has never been in a more deplorable state. Total confusion reigns. Leadership zero, the future is bleak.

So, what does this mean for people like me? Well, I’m one of the lucky ones. As a U.S. Resident, I split my time between Haiti and Florida (and now New York, with the birth of my new little grandson). I have the capacity to seek safe haven anytime the stress is overwhelming and causing my brain to burn-out from fear of being next on the gangs’ long list of victims. The anxiety is relentless. For my people without a U.S., Canadian, or European visa, for those who cannot afford any of it, the sea beckons them to take that journey to safer shores. But that journey is marked by countless dangers, and many of my brothers and sisters, including children and little babies, have perished trying to find a new home, a new place to live in dignity and to dare to dream of a better future. There has been a mass exodus of our youth toward countries like Brazil and Chile that once offered opportunities for our people but now have grown weary of us. Thousands of Haitians make that perilous journey from these countries, through the Amazon, risking their lives to get to the borders of Mexico, and eventually arrive at the borders of Texas where the world recently witnessed horrifying scenes of the Texan border police on their horses, whipping Haitians that illegally crossed their borders, in a scene reminiscent of the days of slavery.

My country’s current authorities seem to have forgotten the valiant fight of our heroes to grant us our independence, men and women like Toussaint Louverture, Henri Christophe, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Sanité Bélair, Alexandre Pétion, François Capois, and so many other nameless and faceless heroes, who have given their blood to liberate Haiti and make it a proud nation of free men and women. I don’t know if we’ll ever see the likes of them again.

Still, as I look back at this past year, I feel blessed despite everything that might have gone wrong. God has insulated me and my family and has brought us out all right this far. I can only pray that He will continue to watch over all of us, guide us and protect us. No one else seems to care. The world is sick of Haiti. So, we’re on our own.

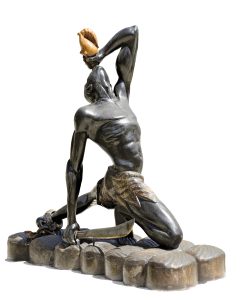

“Le Nègre Marron” sounding the horn of revolution. He is the symbol of Haiti’s slave revolution leading to its independence from France in January 1804.

Sadly true ,countries and lifes seem parallel sometimes

Yes, indeed!